Web site: The Chicago Manual of Style Online

Avoiding Plagiarism

So far we’ve talked about research as the process of gathering information. But the flip side is organizing what you’ve learned and making it available to others. Research is actually a dialogue in which people build upon each other’s work to advance the cause of knowledge for everyone. Plagiarism—which means using other people’s ideas without crediting them—stifles that dialogue. Citation is a way of giving credit to your sources.

▶ Why Giving Credit Matters

There are three main reasons for giving credit to sources in your work.

- To serve your reader: While reading your work, your reader may want to check your facts or learn more about a particular point. Citation allows that.

- To respect your sources: Your sources deserve credit for the work they’ve done. Identifying them in your own writing helps to further their reputation.

- To support your work: Giving credit adds authority to your writing. It shows that you are aware of the scholarly dialogue surrounding your topic, and that you understand how it applies to your own ideas.

▶ What Your Reader Needs to Know

When reading any sort of research—from a newspaper story to a scientific study to a business report—the reader needs to know two things.

- Where did this idea come from? The reader will assume an idea comes from you, the writer, unless it is attributed to another source in a citation.

- How can I check the source myself? This is the single most important point about documentation. Different disciplines have different ways of documenting sources (see pages 396–402). What they share in common, however, is this goal: to make it possible for readers to find and check a source for themselves. Keep this in mind.

▶ What Plagiarism Costs

Without a doubt, plagiarism hurts. Most importantly, it hurts those seeking knowledge, because it severs the tie between a reader and the origins of ideas and information. It also hurts those who created the material, robbing them of the credit they deserve for their ideas.

But plagiarism also hurts the plagiarist. It leads to lazy, shallow thinking and weakens the person’s work. It frustrates the opportunity to root an argument or idea in a dialogue with other scholars. And it can destroy a person’s reputation, earning a reprimand in school or dismissal from a college or a job.

Other Source Abuses

Plagiarism isn’t the only way a source can be misused. Avoid these other source abuses.

▶ Misstating a Source

If you summarize an idea incorrectly, change or misspell words in a quotation, paraphrase inaccurately, or make an error in a statistic, you change the meaning of the borrowed material. This can hurt the reputation of the original author.

▶ Using a Source Out of Context

Another misapplication of source material is to take a statement out of its original context, making it seem to say something that was never intended.

▶ Overusing Source Material

Your writing should present your own thoughts in your own voice, backed up by other sources. If it reads like a string of references, your ideas and voice are lost.

▶ Relying Too Heavily on One Source

If your work relies too heavily on one source, readers may doubt the depth of your research and understanding. Be sure to incorporate a variety of sources into your writing.

▶ “Plunking” Quotations

Quotations should be used sparingly (to support a point or to encapsulate an idea), and they must be smoothly worked into your writing. Do not just “plunk” them into your text, expecting your reader to make the connection.

▶ Using “Blanket” Citations

When you incorporate a source, it must be clear to your reader where that citation begins and ends. For a quotation, that is usually obvious. For a longer paraphrase, however, signal both the beginning and end in your text.

What Plagiarism Looks Like

On these two pages, you’ll find a brief article and ways the article could be plagiarized or abused. Use this as a guide to check your own work for these problems.

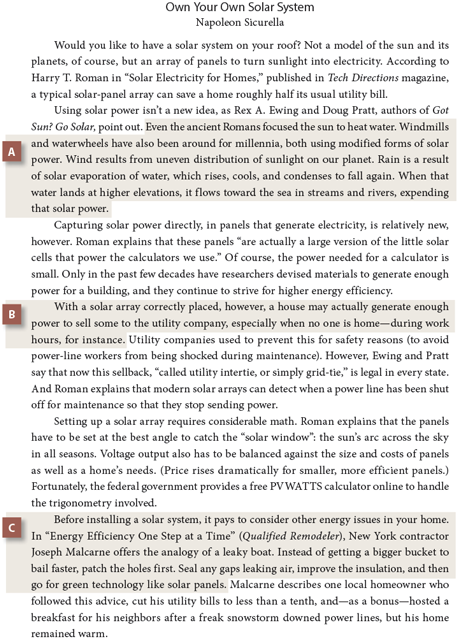

A Copying Text This type of plagiarism uses word-for-word sentences from the original without giving credit.

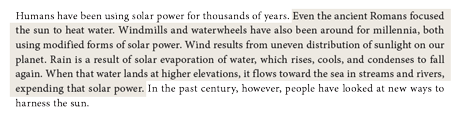

B Neglecting Quotation Marks This type of plagiarism identifies the source but fails to place quotation marks around sentences used word for word from the original.

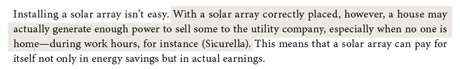

C Paraphrasing Ideas Without Crediting Them This type of plagiarism paraphrases someone else’s ideas but doesn’t identify the source. The reader is left to assume that the ideas are the writer’s.

Additional Plagiarism Offenses

Self-Plagiarism The idea of plagiarizing oneself may seem paradoxical. However, when scholars publish their work, the publisher gains at least some rights to it. Scholars referring to their own work in later writing must credit the original source of publication. Similarly, when students submit a research paper in one class, that paper should not be submitted for an assignment in another class unless both instructors give permission.

Copyright Violation To protect creative works, governments make laws granting copyright and defining fair use. In general, it is illegal to use any part of a copyrighted work without the owner’s permission. “Fair use” laws allow limited exceptions for educational purposes and reviews. Be sure you understand and follow copyright restrictions in your research. The Chicago Manual of Style provides an excellent discussion of this topic.

Note: Using a photograph or graphic without crediting its source is also plagiarism.