To Write an Informative Essay

- Question the communication situation.

- Subject: What specific topic will you write about?

- Purpose: Why are you writing—to explain, to describe?

- Audience: Who will read this essay? What does the audience already know about the topic? What do they need to know?

- Plan your essay.

- Narrow your topic so that you can cover it in a single essay.

- Study similar essays so that you understand the structure.

- Research your topic.

- Searching: Consult primary and secondary sources as needed to learn about your topic. (See pages 376–391.)

- Focusing: Form a thesis statement, expressing a specific thought about the topic of your essay.

Topic: Mayan math

Thought: used a unique counting system

Thesis statement: As a foundation for their astronomical and calendar calculations, ancient Mayans relied on a unique counting system based on three symbols.

- Create the first draft of your essay.

- Open with a paragraph that introduces your topic, grabs your reader’s attention, and states your thesis.

- Follow with middle paragraphs that support your thesis with appropriate details.

- Organize the details in an effective order (see page 188).

- Close with a paragraph that revisits your thesis.

- Improve your first draft.

- Evaluate your first draft.

Purpose: Does the essay effectively fulfill your purpose?

Audience: Will the essay hold the reader’s interest?

- Revise your writing.

Rewrite sentences that are confusing or unclear.

Add connecting words or transitions.

Cut parts that are off the topic or do not further your thesis.

- Evaluate your first draft.

- Present the final copy of your essay on a personal blog or a classroom wiki.

Informative Essay

An informative essay is also known as an expository essay. This type of writing explains an idea or demonstrates how something works. It is often assigned during high school and in college courses.

A New Age of Robots

The beginning introduces the topic in an interesting way and includes a thesis statement (underlined).In a poignant scene in the 2004 science fiction movie I, Robot, Sonny, a robot, asks Will Smith’s character why humans wink at each other. Smith tells the robot: “It’s a sign of trust. It’s a human thing. You wouldn’t understand.” Smith’s terse response reflects what many people think of robotic technology: Sure, robots can perform some tasks like a human, but they certainly cannot think like a human. Such a sentiment is evolving into a myth. Today’s computer scientists and robotic engineers are creating robots capable of advanced human thinking.

Each middle paragraph focuses on a different supporting example.One robot showing signs of artificial intelligence (AI) is called RuBot II. RuBot II is nicknamed the “Cubinator” because it can solve Rubik’s Cube puzzles in record times. How does it work? After a human scrambles the cube, RuBot II picks it up, raises it to eye camera level, and scans all sides of the cube. In less than a second, RuBot II computes a solution to the puzzle using an algorithm. Next, RuBot II’s hands deftly solve the puzzle in less than 20 moves. As computer scientist Aaron Sloman told New Scientist magazine, “Human brains don’t work by magic, so whatever it is they do should be doable in suitably designed machines.”

Another robotic innovation is able to predict the intentions of its human partner. European researchers at JAST have built a robot capable of observation and anticipation. In JAST experiments, the robot and its human partner interact to build basic model airplanes. The JAST robot’s computerized brain already knows the task, but it observes the partner’s behavior, maps it against the task, and eventually learns to anticipate the partner’s actions and spot errors when the partner does not follow the correct or expected procedure. For example, by observing how its human partner holds a tool or model part, the robot is able to predict how the partner intends to use it. The JAST project is groundbreaking because it demonstrates tangible progress in creating a robot that is proactive in its interaction with humans.

Maybe the most advanced robot in the world is Ecci, a C3PO look-alike with synthetic muscles, tendons, and bones. Ecci also has the visual capability of humans and the brain capacity to correct its own mistakes. Researchers at the University of Zurich built a computer into Ecci’s brain that allows it to study and analyze its own behavior. If, for example, Ecci moves in a way that causes it to stumble or drop something, the computer is able to evaluate the behavior and correct it so that it does not happen again. Ecci’s unique engineering and correction capacity point to a future where robots could function in an unstructured human environment.

The ending revisits the thesis and discusses its future implications.However, even though today’s robots can imitate some specific aspects of human intelligence, they are still not capable of the artificial intelligence displayed by Sonny in I, Robot. Computer programming and algorithmic methods give robots limited ability to solve problems, interact with humans, and learn. But the technological advances necessary to give them the capacity to reason, to form new ideas, and to think critically confound today’s scientists and engineers. Why? Natural intelligence is still largely an enigma—we simply do not understand how it works. At the same time, continued advancements in robotics indicate that a world where humans and robots interact on a daily basis is no longer a matter of pure science fiction.

Building Essays

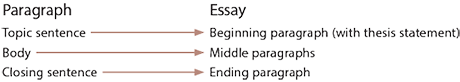

Essays provide a forum to advance your ideas, and, in turn, advance your thinking. An essay has a clear beginning, middle, and ending. The following chart compares the working parts of paragraphs and essays. The chart below examines the parts of essays in greater detail.

Basic Structure of Essays

|

|

|

|

|

|