74

Speaking

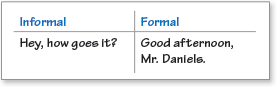

Much of human communication is spoken—whether during a friendly conversation, a news broadcast, a lecture, or a negotiation over the price of a car. The way that you speak depends on the communication situation. For example, if you get pulled over by a police officer, you will speak differently than if you are talking to a friend at your locker. Each situation calls for a specific level of formality.

Formality

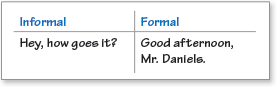

Formality relates to all aspects of the communication situation. The chart below discusses levels of formality and tells the kind of situation each level fits:

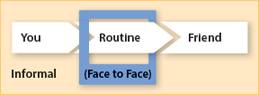

Informal

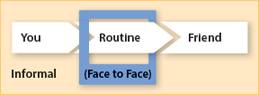

Relaxed language with slang, contractions, humor, personal pronouns, and fragments.

▶ Use for routine messages delivered face-to-face with friends.

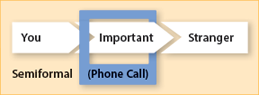

Semiformal

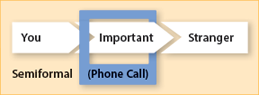

Language with some contractions and personal pronouns, occasional humor.

▶ Use for important messages to strangers; for example, on the phone.

Formal

Correct, serious language using complete sentences and avoiding slang.

▶ Use for serious messages to authorities or groups and in other formal contexts.

Your Turn Think about situations in which you speak. Write down an informal speaking situation, a semiformal one, and a formal one. Then, for each situation, write an example sentence that uses the appropriate level of formality.

Example:

Formal: An award speech—”I would like to thank Principal Parker, the staff, the awards committee, and the students of BHS for selecting me for this honor.”

75

Speaking One-on-One

Many one-on-one conversations require a formal speaking style—for example, meeting with a guidance counselor, interviewing someone, or talking to a college admissions director. Follow these tips for formal one-on-one conversations:

Before . . .

- Analyze the situation. Think about whether you are representing yourself or a group (like the school newspaper or the student council). Think about the subject, your reason for discussing it, and the context.

- Learn about the audience. Find out what the person knows and needs to know about the topic. Think about what the person wants to get out of the conversation. Learn how to correctly pronounce the person’s name and which courtesy title to use (Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., Coach).

During . . .

- Greet the person. Introduce yourself, shake the person’s hand, and thank the person for speaking with you.

- Be polite and respectful. Use please and thank you and show that you appreciate the person’s time.

- Make eye contact. Give the other person your full attention and smile. Keep your facial expressions open and interested.

- Use appropriate body language. Stand or sit with upright posture. Nod your head to show that you are paying attention. Use gestures when appropriate.

- Speak clearly and calmly. Use formal language and pronounce words carefully. Avoid slang and other informal constructions.

- Focus your conversation. Stay on topic and remember your reason for speaking with the person. Avoid straying into other issues.

- Thank the person. End the conversation by telling how much you appreciated the opportunity. Shake the person’s hand once again.

After . . .

- Reflect on the conversation. Review the main points of the conversation and write down any part that you will need to remember.

- Follow up, if appropriate. You can send an email thanking the person again, or you can send a message requesting any clarification you need.

Your Turn Think about appropriate formality for speaking with a friend or a counselor. Create a chart of informal and formal phrasing.

76

Speaking in a Group

In school and in the workplace, you’ll often be asked to participate in small-group discussions. Follow these tips to get the most out of these communication situations.

Before . . .

- Analyze the situation. Think about what the group is trying to accomplish, what you will discuss, and where the conversation will take place.

- Think about the group members. Make sure you know everyone’s name. Consider what the other members want from the group.

During . . .

- Engage in the conversation. Speak and listen, make eye contact, and stand or sit in an upright posture that shows your interest. Avoid slouching and nervous tapping.

- Start sentences with “I” instead of “You.” In this way, you avoid sounding accusatory and signal that you are speaking for yourself.

- Take turns. Don’t dominate the conversation, but don’t remain silent either. If you see that someone hasn’t gotten a chance to speak, prompt the person: “Jana, what do you think of this idea?”

- Be polite. Make sure that everyone feels welcome and safe to contribute. Recognize when someone has a good suggestion. Apologize when needed.

- Focus on ideas, not on personalities. Direct comments and questions to the issue you are discussing rather than to the people involved in the conversation.

- Stay on task. If the conversation veers off topic, gently bring the group back to the issue at hand: “Let’s set that issue aside until we make a decision about which approach we’re going to use.”

- Facilitate the conversation. Keep the group moving forward by nudging the conversation along: “It sounds like everybody agrees with this suggestion—is that true? All right, so what next steps should we take?”

After . . .

- Review the discussion. Write down decisions made and major topics discussed. Think about whether the group completed all the work it needed to do.

Your Turn Think about a recent group discussion you have had. How did it go? Which of the tips above were evident in the discussion? Which tips could have improved the conversation?

77

Speaking to an Audience

In school and out, you will occasionally need to speak to a large group. Careful preparation will equip you for success. Follow these tips for giving a speech.

Before . . .

- Analyze the situation. Think about the message you want to deliver. What is the main point? What support do you need? Consider the place where you will deliver your speech and the audience who will be listening.

- Know your topic. Carefully research your topic and gather the information you need to present.

- Prepare your speech. Write out your speech word for word if you wish, or prepare note cards to help you remember what you want to say.

- Prepare visuals. Create a slide show to accompany your speech, or provide other visuals to get your point across.

- Practice. Videotape yourself and watch your delivery. Make your presentation in front of family or friends and use their suggestions to improve your delivery.

During . . .

- Stand tall and look out just above the audience. Don’t slouch, and remember to make eye contact occasionally.

- Speak loudly and slowly. Project your voice to the back of the room. Pronounce words clearly.

- Eliminate ums and uhs. Speak without distracting hedging sounds.

- Use visuals. Present visuals that get your point across.

- Engage the audience. Consider asking one or more audience members to come up and get involved with a demonstration or an activity.

- Videotape the presentation.

After . . .

- Reflect on the presentation. Watch the video if you have one. Think about what parts went well and what parts did not.

- Consider ways to improve. Think about what you will do differently in your next presentation.

Your Turn Think about a speech you have given or one you may give in the future. Which of the tips above is most important to you? Which do you already do naturally?

78

Parts of a Speech

Every speech needs to have a beginning, a middle, and an ending. You can write out the whole speech as a manuscript, or you can use note cards like those below.

The first card includes the complete introduction.

1

Introduction (show first slide)

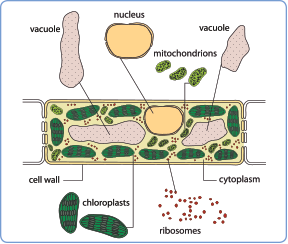

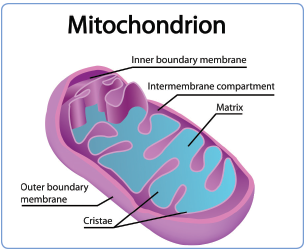

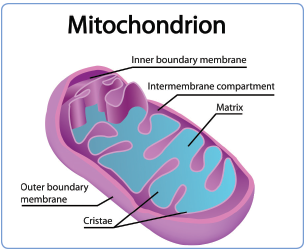

In every one of our cells, we have two types of DNA. Most people are aware of the DNA in a cell’s nucleus, but they may not know of the mitochondrial DNA inherited from the mother alone, which is used to trace matrilineal descent.

Mitochondria provide power to cells by converting the chemical energy of food into adenosine triphosphate—a form cells can use.

The middle cards list main points.

2

Endosymbiotic Theory

- Mitochondria as prokaryotic bacteria

- Eukaryotic cells engulfed early on

- Mitochondria in all animal and plant cells

3

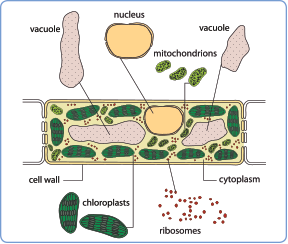

Chloroplasts and Plants

- Chloroplasts conduct photosynthesis

- Came from cyanobacteria

- Similar endosymbiotic event

- All photosynthesizers have them

The final card includes the complete closing.

4

Closing (show last slide)

The simple cell is anything but simple. In plant cells, two separate endosymbiotic events have led to the inclusion of mitochondria and chloroplasts. In our own cells, the presence of two types of DNA demonstrates our connection to very early bacterial forms. They live on within us, providing energy for everything we do.