“Look, Mom! See the turtle! He is scaly!”

Spend a day with a small child, and you will hear many such observations. That’s because all of us have an innate human desire to teach. Somehow what we learn isn’t real until we share it with someone else.

“Watch what I can do! Let me show you how!”

The exclamation points are almost mandatory, because we want to teach. “Show and tell” is one of the most popular times in elementary school—the chance for students to become teachers. And much of the appeal of social media is allowing middle and high school students to share what they have discovered.

“I want to show you something. You’ll never believe this—it’s so COOL!”

Teaching—Unique to Our Species

You’ve heard the expression, “Monkey see; monkey do.” It’s quite literally true. Great apes learn by mimicking what they see, but they don’t actively teach. Why not?

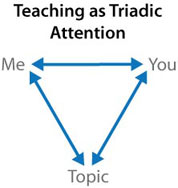

The act of teaching requires “triadic attention.” When you teach, you have to pay attention to three things—yourself, the other person, and the topic you are teaching. If you lose track of any of the three parts, the teaching moment is lost. Triadic attention is a hat trick that other species can’t maintain for long. Human beings, however, are capable of this feat even before they can speak. That’s why toddlers do so much pointing—to teach you about what they are seeing. Teaching is so central to who we are that perhaps our species should be renamed Homo pedagogues.

Read more