384

Using Primary Sources

Depending upon your research purpose, primary sources may play a role.

Observing an Event or Exhibit

If you want to understand a Shakespeare play, you can read the script, but nothing compares to seeing it performed. Similarly, while you can read a book about Egyptian funerary items, nothing compares to seeing them in an exhibit. Such first-person experience adds a primary-source element to your research.

Tips for Observing

- Prepare by learning what you can beforehand. The more you know before going into the event, the more aware you will be during it.

- Experience the event fully while you are there. Pay close attention both to broad aspects and to details. If any handouts are available (such as programs, pamphlets, or menus), be sure to gather them as well. Besides providing additional detail, they can help you when documenting the event.

- Review the event as soon as possible after the experience. Record everything you remember, including your own feelings and thoughts.

Viewing Historical Items

Historical documents, such as diaries, personal correspondence, maps, legal papers, and so on, can provide insights into many scholarly topics.

Library of Congress Web Site: The U.S. Library of Congress maintains a collection of documents, photos, sound recordings, and more. Much of this material is arranged into presentations by topic or period, and all of it is searchable. You will find the Library of Congress Web site at

www.loc.gov.

Library Special Collections: Many libraries (especially college libraries) have special collections of original documents and other historical items. These may include rare books, personal journals, correspondence, maps, and so on. Items like these can give you a perspective on your topic that is not available elsewhere.

Typical Library Rules for Special Collections

- Material must be viewed in a special room and cannot be checked out.

- Backpacks, briefcases, coats, purses, and such must be left in lockers outside the reading room.

- No food or drinks may be taken into the special collections area.

- Only one item can be viewed at a time. A request slip must be filled out for each.

- No pencil marks may be added or erased, books must be laid flat on the reading table, gloves may be provided to protect pages, and so on.

385

Conducting Interviews

By interviewing an expert, you can ask questions and find answers you may have difficulty finding anywhere else. Carefully chosen quotations from an expert can also add authority to your research report.

Types of Interviews

- Live: Whether in person or by video conference, phone, or text chat, a live interview allows you to adapt questions and lines of inquiry as you go.

- Correspondence: An interview by mail or email is less spontaneous than a live interview, but it provides a record of questions and answers.

The Interview Process

Before the interview . . .

- Do basic research. Learn as much as possible about your topic. Don’t waste the interviewee’s time with basic questions.

- Prepare a list of questions. The better the questions, the better the answers. Write open-ended questions that invite extensive answers.

- Identify possible experts. Refer to your basic research to determine good candidates for an interview.

- Arrange for an interview. Contact one or more people from your list, identify yourself and your purpose, and politely ask for an interview. Schedule it at your interviewee’s convenience.

During the interview . . .

- Be polite. Remember that the interviewee is doing you a favor. Experts are often very busy people, and taking time for an interview is a kindness.

- Ask permission to record and quote. While most interviewees won’t mind, never assume that is the case. Always ask for permission.

- Pay attention. In a live interview, listen carefully and take notes. In a correspondence interview, carefully consider the person’s answers. In either case, ask for clarification if needed.

- Be prepared to reword a question if the interviewee doesn’t understand. Also ask follow-up questions if you need more information.

- Review your notes before ending the interview. Make sure that they are accurate and that you haven’t forgotten anything.

- Ask for recommendations of other sources of good information.

- Thank your interviewee for his or her help.

After the interview . . .

- Send a thank-you note to the interviewee.

- Review your notes and politely follow up with any further questions.

- Consider offering a copy of your finished work to the interviewee.

386

Using Surveys

A survey is a detailed study used to gather data (statistics, opinions, or experiences) about a topic. The U.S. census conducted every 10 years is an example of a fact-finding survey. The Nielsen television ratings are based on another sort of survey. A public opinion poll held outside an election facility is yet another. You may also encounter surveys online, in a department store, or elsewhere. And you may conduct your own survey to gather information about your own research topic.

While the answers to some survey questions may be subjective (“What is your favorite fruit?” “How would you rate our customer service on a scale of 1 to 10?”), preparing a survey and compiling responses is serious business. Scientists and other scholars seek a statistically significant number of responders and calculate a margin of error in the results. To conduct your own survey, follow these steps:

Survey Guidelines

- Identify the purpose and audience for your survey: What do you want to learn, and whom do you want to contact?

- Form the survey according to your purpose.

- Write questions that are clear and ask for the right type of information.

- Word questions so they are easy to answer.

- When possible, offer options to circle, underline, or click.

- Consider two types of questions.

- Closed-ended questions usually provide options and are easy to answer. (Yes-no, multiple choice, true-false, and fill-in-the-blank questions are examples.)

- Open-ended questions ask survey takers to write out short answers.

- Arrange the information in a logical way.

- Start with a brief explanation of who you are or whom you represent, the purpose of the survey, and how to complete and return it.

- Number and label all of the information that follows so the survey is easy to understand.

- Provide enough space for readers to make their responses.

- Give it a test run.

- Have a few classmates or friends complete the survey.

- Revise it as needed.

- Carry out the survey.

- Distribute it to the intended group.

- Collect and evaluate the responses.

387

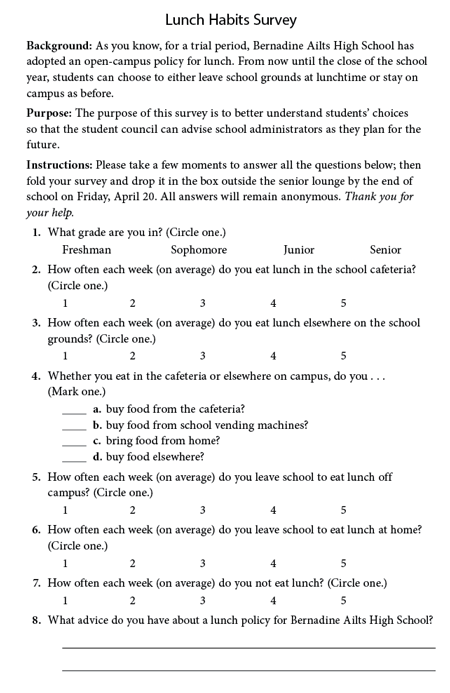

Sample Survey

This survey was prepared by student council members to gather information about students’ lunchtime habits. The purpose is further explained in the survey itself.

388

Conducting Experiments

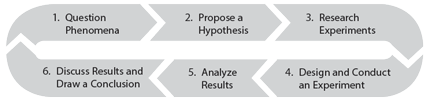

The scientific method is an inquiry strategy that can help you find the answers to research questions. Here are the steps involved:

The Scientific Method

Recursiveness in the Scientific Method

As step 6 indicates, the scientific method is often recursive, with the results leading to more questions (step 1), new hypotheses (step 2), more research (step 3), and new experiments (steps 4–6).

Steps of the Scientific Method

- Question PhenomenaAs you study any topic, questions naturally arise. Allow what you have been learning to spark curiosity about what you observe. Ask many questions and select the one that most interests you.

Example: Is plant growth affected by music?

- Research Experiments Before designing and conducting an experiment, you should discover what work other people have already done on the subject. (This is why the APA Style Manual suggests that writers “describe relevant scholarship” in the introductions to their articles. See pages 398–399for more about APA documentation style.)

Example: Before conducting an experiment about the effect of music on plants, search for any previous studies and discussions of the topic. As it turns out, many people have written about the effects of music on living creatures, and several have experimented specifically with plants. Some suggest that music affects the human caretakers directly and the plants indirectly. Others have studied only specific musical tones.

389

- Design and Conduct an Experiment A good experimental design controls as many variables as possible so that the results can be attributed to one specific variable or cause. (See the discussion of variables on pages 20–21 and 55.) This is why most experiments include a “control group.” (In medical testing of a new drug treatment, for instance, one group of patients will receive the actual drug, while another otherwise identical group will receive a placebo.)

Example:To test the possible effect of music on plants, our experiment will

- focus on one specific plant type—indoor tomato plants;

- start each plant from the same packet of seeds;

- make sure each has the same environment of soil, water, light, and temperature;

- expose each to a different type of music at different volumes 24 hours a day, using the same type of music player for each;

- keep one plant in a quiet room, as a control;

- let all plants grow until the fruit appears on each; and then

- compare indications of health, including size, color, and number of tomatoes.

- Discuss the Results and Draw a ConclusionLike any other sort of research, while some experiments will offer a clear yes or no answer, most will raise new questions to explore or suggest design revisions of the same experiment.

Example: Our “effect of music on plants” experiment might prove inconclusive for tomatoes, leaving us to wonder about other sorts of plants. Or one of the tomato seeds might not grow at all, encouraging us to redesign the experiment, including more than one plant in each music room to provide a larger, more accurate sampling.

Usually, “discuss the results and draw a conclusion” means writing a paper or an article about the experiment. In this way, you contribute to the background research that others can use in their own experiments about the topic.

Applications of the Scientific Method

This six-step process is useful beyond what you might think of as pure “science.” Statisticians use the process to study Web-search patterns, for instance. Psychologists use it to study human behavior. Survey makers use it to draft and revise survey questions. You can apply it to nearly everything you’re curious about.