Web Page: Research Paper

Web Page: Writing a Research Paper

Web Page: MLA Formatting and Style Guide

Web Page: MLA Documentation Guide

Limited topic + debatable claim/statement = working thesis

Purpose: Does the paper achieve your goal?

Audience: Will the paper engage and enlighten readers?

Rewrite parts that are confusing or unclear.

Add more details to explain your topic more fully.

Cut parts that don’t support your thesis.

Reorder parts that could be more effectively arranged.

Review your documentation. (See pages 396–402.)

Check your writing for accuracy using pages 190–195 as a guide.

The following research paper on Hmong Americans follows MLA style. (See pages 396–397 for different documentation styles.)

Wadsworth 1

Beth Wadsworth

Mr. Dan Meadow

American Studies

17 April 2012

The beginning introduces the topic and leads to the thesis statement (underlined.)Understanding Hmong Americans

In the melting pot of cultures in the United States, Hmong Americans are among the most misunderstood and enigmatic ethnic groups. Hailing from mountainous regions in southern China, Thailand, Laos, and Vietnam, the Hmong population in America is concentrated mostly in three states—California, Minnesota, and Wisconsin. Such isolation has contributed to outsiders’ misconceptions about these people. Besides the isolation, unfamiliarity with Hmong history, including the people’s pro-American involvement in the Vietnam War, has contributed to this misunderstanding. Hmong Americans are a proud yet evolving culture wrestling with old-world tradition and new-world Americanism.

To begin to understand the American Hmong population, one must consider where they came from and how they got here. Throughout history, Hmong people have never had a nation of their own but have always been motivated by autonomy. When the eighteenth-century Hmong population living and farming in the highlands of southern China feared for their independence, they fled south into Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam. When Laos experienced civil war in the 1950s and 1960s, the Hmong sided with the government, fearing a communist regime would disrupt their independence (Bankston). During this period of unrest, the United States sent elite

Wadsworth 2

soldiers to train the Hmong people to oppose Vietnamese and Laotian communists. This partnership would later become an integral part of the Secret War in which the United States CIA recruited Hmong tribesmen to block North Vietnam’s access to the Ho Chi Minh Trail supply corridor in Laos (Her and Buley-Meissner 79).

The war decimated the Hmong adult population. When Laos fell to the communists and Americans fled Vietnam, the Hmong were left to fend for themselves as the Pathet Lao communists and North Vietnamese threatened to wipe them out. More than 100,000 Hmong fled Laos to Thai refugee camps, and many were killed along the way. Chang Yang was a refugee who survived a perilous swim across the Mekong River in Laos to the shores of Thailand:

An excerpt is indented to set it off from the text.We had a lot of people get shot while crossing the river. We used the moon for light. Babies were crying. People were drowning. And enemy soldiers [had] a boat that they used to circle around looking for these people. Whoever they [saw], they [shot] or pulled them off and took them back to Laos. (“Bridging the Shores”)

An estimated 30,000 Hmong were killed in the war in Laos, a devastating loss for an already small population (“The Secret War”).

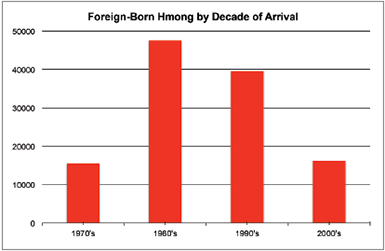

The period after the Vietnam War marked the first wave of Hmong migration to the United States, but a much larger migration occurred in the mid-1980s when the United States passed the Refugee Act of 1980 (Lai and Arguelles). The Act permitted family members of the Hmong Secret Army from the Vietnam War to immigrate to the United States. By the 1990s, a bitter debate raged about what to do with the thousands of Hmong who remained in refugee camps in Thailand. At the time, the Thai government threatened to forcibly send Hmong refugees back to Laos, where they expected to be met with discrimination and violence (George and Mai). While Congress and the United Nations debated

Wadsworth 3

what to do with the Thai-based Hmong, many refugees fled to other parts of Thailand, while others hid in the forests of Laos. Finally, in 2004, the United States granted immigration rights to 15,000 Hmong from one of the last major refugee camps in Thailand. Though many Hmong were reunited with family members, the unrest in South East Asia still weighs heavily on the Hmong people living in the United States (George and Mai).

During the first wave of Hmong migration shortly after the Vietnam War, American resettlement agencies dispersed Hmong immigrants to major cities throughout the country. Statistics make the report informative.The first Hmong encountered racism from Americans who did not know about the integral role the Hmong had played in fighting communism during America’s Secret War (“Bridging the Shores”).

When the second, much larger wave of Hmong immigrants reached America in the mid-1980s, most of the Hmong population had reassembled in small northern California farming towns. And in the 1990s, many Hmong settled in Minnesota and Wisconsin. Today, of the 260,073 Hmong living in America, 91,000 reside in California, 66,181 in Minnesota, and 49,240 in Wisconsin (“2010 Census”).

The population’s concentration in a select few states is attributed

Wadsworth 4

to two main factors. First, fertile soil in California and the Midwest attracted Hmong farmers, the most prevalent occupation in their homeland. Second, Hmong culture reveres family interdependence. Hmong family ties are extensive and loyal. They tend to live together with grandparents, children, grandchildren, and cousins all under one roof (Lai and Arguelles). Such a living arrangement stems from a clan mentality of self-governance and self-reliance dating back to the Hmong’s time in ancient China. In fact, clan membership still plays a major role in the organization of Hmong populations. Hmong Americans are organized into 19 different clans. Membership is passed along through birth, and Hmong within the same clan are not allowed to marry (“The Secret War”).

Early Hmong immigrants struggled to assimilate in American culture. Beyond bouts with racism, Hmong customs clashed with American culture and with U.S. laws. For example, in traditional Hmong culture, girls marry between the ages of 14 and 16, which conflicts with marriage laws in the United States. Second, extended Hmong families preferred to live in crowded households that often exceeded housing regulations. Last, language barriers put the entire Hmong family structure in flux. In Laos, the father was the most respected figure in the family. He made the decisions, and they were final. In America, elders relied on their children and grandchildren as translators. Translations between the youth and elders were not always correct, and household misunderstandings resulted (Fass 1).

Finding jobs proved particularly difficult for early Hmong immigrants. In 1990, almost two-thirds of Hmong Americans lived below the poverty line (Bankston). The Hmong’s agrarian background meant the vast majority of immigrants could neither read nor write and had no experience with industrial jobs. Farming in the United States

Wadsworth 5

required large plots of land and expensive equipment, neither of which were affordable for Hmong immigrants. Further contributing to the Hmong’s financial struggles were the large households. In 1990, Hmong households averaged 6.38 individuals compared to 3.73 in the average Asian American family, 3.48 in the average black family, and 3.06 in the average white American family (Bankston). Producing a small income for large households resulted in more than half of Hmong families relying on federal welfare programs to stay afloat (Her and Buley-Meissner 121).

As the economy improved in the late 1990s, so did Hmong employment. Census data reflects upward socioeconomic movement, though the Hmong’s poverty rate is still among the highest in the country (Lai and Arguelles). Increasingly, Hmong adults, including women, have taken jobs outside of the home. Some Hmong have opened their own small businesses, and Hmong farmers have profited from the local farm-to-table food movement (Bankston). As more Hmong receive formal education, socioeconomic conditions are expected to improve.

In terms of education, 61 percent of Hmong Americans have graduated from high school, a number that is expected to rise as more American-born Hmong reach their teens. However, many Hmong struggle with the English language, and there are not enough bilingual Hmong teachers available (Vang 3). The writer’s discussion reaches the present day.Language deficiency and poor socioeconomic conditions are the greatest barriers to academic achievement, and the Hmong Americans’ academic advancement lags in comparison to that of the general public, especially at the post-secondary level (5).

Today, Hmong youth are more Americanized than the previous generation, which is a point of conflict between Hmong elders and youth. In fact, about 60 percent of the 260,073 Hmong living in the

Wadsworth 6

United States were born here. American-born Hmong are less bound by traditional Hmong customs than first-generation immigrants are (“Bridging the Shores”). But the elders, who endured bloodshed and poverty to make it to America, worry that the Hmong culture will soon be washed away. Addison Lee told Wisconsin Public Radio, “The gap between the youth and the elderly is broad, whether it is religion, weddings, or how you deal with certain issues” (“Bridging the Shores”). Young Hmong Americans are campaigning for women’s rights and speaking out against domestic abuse, as well as rejecting some traditional customs such as teenage brides (Lai and Arguelles). Still, second-generation Hmong are not completely rejecting old traditions. The first-born daughter in a family is still responsible for taking care of the household when the mother is at work, marriage dowries are still commonplace, and Hmong Americans still celebrate Hmong holidays.

What the future holds for Hmong Americans is unknown. The Hmong are still one of the newest ethnic groups in America. While economic and educational opportunities are rising, workplace and academic achievements lag. Moving forward without diminishing their unique culture will remain a challenge. Hmong elders worry that Americanized youth will forget the sacrifices they made to preserve their culture in this country. Such sacrifices deserve to be commemorated by both Hmong and non-Hmong Americans, for thousands of Hmong gave up their lives to support the United States’ fight against communism. The next chapter in the Hmong American experience is still unwritten, but the Hmong, as they always have, will write it together.

Wadsworth 7

Works Cited

Entries appear alphabetically, with runover lines indented.Bankston III, Carl L. “Hmong Americans.” Countries and Their Cultures. 14 March 2012. Web.

“Bridging the Shores: The Hmong-American Experience.” Wisconsin Public Radio. WERN, Madison, 2008. Radio. Quotation marks surround titles of short works. Italics set off long works.

Fass, Simon M. “The Hmong in Wisconsin.” The Wisconsin Policy Research Institute Report 4.2 (1991): 1. Print.

George, William Lloyd, and Chiang Mai. “Hmong Refugees Live in Fear in Laos and Thailand.” Time 24 July 2010. Web.

Her, Vincent K., and Mary Louise Buley-Meissner. Hmong and American: From Refugees to Citizens. Minneapolis: Minnesota Historical Society Press, 2012. Print. Designations such as “Print” and “Web” indicate the delivery method of sources.

Lai, Eric, and Dennis Arguelles. The New Face of Asian Pacific America: Numbers, Diversity, and Change in the 21st Century. Los Angeles: UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press, 1998. Web.

“The Secret War.” The Hmong: An Introduction to Their History and Culture. The Cultural Orientation Project. 28 July 2004. 14 March 2012. Web.

“2010 Census Hmong Populations by State.” Hmong American Partnership 2010. 20 March 2012. Web.

Vang, Christopher T. “Hmong-American K-12 Students and the Academic Skills Needed for a College Education: A Review of the Existing Literature and Suggestions for Future Research.” Hmong Studies Journal 5 (2004): 1-31. Web.

Web Page: Research Paper

Web Page: Writing a Research Paper

Web Page: MLA Formatting and Style Guide

Web Page: MLA Documentation Guide

© 2014 Thoughtful Learning