536

To Create Game Designs

- Question the overall situation for the game.

- Subject: What is the topic or genre? What information will the game draw on?

- Purpose: What should the game accomplish? Is it intended to train? Test? Entertain? Recruit?

- Audience: Who will play the game? What will they expect from it? What difficulty will they be prepared for? What level of instruction will they need?

- Plan your game by contemplating the bigger picture. Make a note of design goals—including story, mood, game mechanics, victory conditions, and so on.

- Research your topic.

- Gather information about the subject being simulated. Familiarize yourself with other games in that field.

- Understand the odds of any randomizers. (Two standard dice create a bell curve, with a 1 in 36 chance of a rolling a 2, and a 1 in 6 chance of rolling a 7.)

- Create your game. Design a prototype for play-testing.

- Board and card games involve one or more players and may be competitive or cooperative. See the next page for tips on creating board and card games.

- Computer game levels are often fan-created add-ons to existing products. See page 538 for tips on creating computer game levels.

- Role-playing games let players describe their characters’ actions in a fictional adventure led by a game host. See page 539 for tips about role-playing games.

- Improve your game.

- Evaluate your game.

Is it fun and engaging? Do people want to play again?

Is it understandable? Can people play without you present to explain rules? Are people happier, more skilled, or more knowledgable after having played?

- Revise your game.

Remove any distracting or boring parts.

Rearrange rules or parts that may be out of place.

- Redo ideas or game text that is unclear or confusing.

- Add any missing rules, explanations, or background about the topic.

- Perfect your game, making it clean, clear, and attractive.

- Present your game to the public, publishing it online or having it manufactured. (Go to thoughtfullearning.com/h536 for more help publishing games.)

About Educational Designs: Nearly all types of games can be used to teach. When designing an educational game, be sure the learning suits the context. Don’t make “chocolate-covered broccoli,” in which a task like multiplying numbers is disguised as a game like “Climb the Mountain!” Instead, use the mountain as a setting for plotting a climb (calculating trajectories, time required, food and oxygen needed, and so on).

537

Board Game

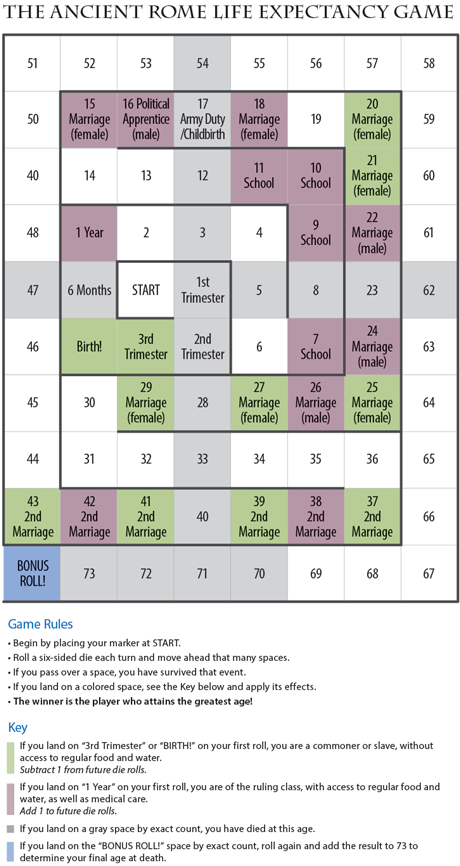

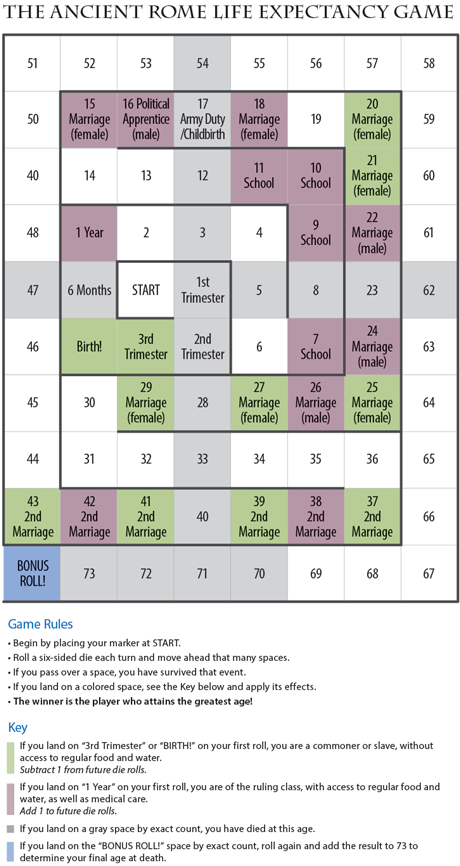

Board games range from abstract (such as Checkers or Go) to simulations (such as Risk or Life). Most are some mix of those two. Chess, for example, is abstract, but pieces simulate kings, queens, and so on.

In this board game, a student simulates life expectancy in Ancient Rome. The spiralling game track represents higher mortality rates in early years. Romans who survived early hazards were statistically more likely to reach old age. For added interest, other details not specifically related to survival are included.

Card Game

Rules for common games can be adapted to your own purposes. A Cribbage game with the “Show” portion of scoring removed can simulate a fencing match of foils or epees. Or you might create a simulation of 19th century mining, using the spades suit as digging tools, hearts as miners, diamonds as ore, and clubs as guards.

538

Electronic Game

There are many opportunities for you to create electronic games or game levels. Here are a few things to bear in mind:

- Consider the Mood: Images, text, and any audio should work together to maintain an appropriate feeling.

- Consider the Mission: Players should know what they need to do to win, whether it is surviving for a set period, traveling to an end point, solving a puzzle, or gathering a list of items.

- Consider the Map: Watch a few people play your game or level. If many of them fail at a particular point, revise that area. On the other hand, if most of them easily complete the game, adjust the difficulty.

▶ Navigation Games

Many computer games mainly involve moving from point A to point B while avoiding traps and solving puzzles. One of the first examples to include a level editor was Atari’s Lode Runner. A more current example is Little Big Planet, which includes a drag-and-drop interface for building levels players can share online.

▶ Real-Time Strategy Games

Some real-time strategy games are simple “tower defense” games, involving careful use of materials and personnel to defend against invaders. Others involve managing resources to capture new territory. Many of the most popular—Command and Conquer, World of Warcraft, Civilization, and so on—combine both requirements. These last three also include map editors so that you can create your own missions. For an open-source alternative, see www.zero-k.info.

▶ Point-and-Click Games

Using an HTML editor, you can create your own which-way or pick-a-path adventure games, mixing text and images on each page. Or you can use image mapping code to hyperlink parts of an image, allowing players to click on different areas for different results. With the addition of javascript coding, you can even simulate dice rolls and keep track of character equipment and statistics.

▶ Hidden-Object Games

Hidden-object games present the player with a complex image and ask that specific items be found within it. As each item is clicked, it disappears from the screen. You can create your own simple hidden-object game for free at hidenseek.viquagames.com, or build an HTML document with images in clickable layers.

539

Role-Playing Game

Role-playing games (RPGs) ask players to imagine themselves as characters in a fictional setting.

- Tabletop role-playing involves rule books and randomizers such as dice or cards. Players describe or narrate their characters’ actions, and a “game master” (GM) represents the world around them.

- Mystery parties and live-action role-playing (LARP) are more theatrical examples, with players portraying their characters’ actions, often in costume.

- Electronic role-playing games may be text-based chat sessions with few if any rules. Or they may be either single-player computer games or massively multi-player online role-playing games (MMORPGs), both focused on quests and character enhancement rather than collaborative storytelling.

Role-playing is also often used as a training or testing technique, particularly for healthcare workers, emergency staff, and military personnel.

A Simple Example

For a very easy role-playing party game, find the rules for “Werewolf” online. You can assign character roles using several cards from a standard deck: a king for the moderator, two queens for the werewolves, a jack for the seer, and one number card for each of the villagers.

Designing a Role-Playing Game Adventure

Most role-playing design involves preparing adventures, rather than inventing rules. Use the following steps to prepare and run your own adventure.

- Choose a genre and rules. Do you intend to run a fantasy, science fiction, or historical adventure? Do you prefer simple, cinematic rules or more complex, realistic ones? Once you have chosen a set of rules, familiarize yourself with them so that you can handle questions during play.

- Decide on a scope for your adventure. An adventure to be played in one evening must be simpler than one intended to stretch over multiple weekly sessions.

- Invent adversaries. Unlike fiction, in which the author controls all characters, role-playing is collaborative storytelling. The game master’s role is to invent one or more villains and their goals. The players’ characters will try to thwart those adversaries.

- Devise a plot. With the adversaries’ goals in mind, sketch a plot of events. Imagine when and where the players’ characters might encounter those events, and prepare scene descriptions, henchmen to overcome, bystanders to save, rewards for success, penalties for failure, and so on.

- Run your adventure. Host a group of friends to play your adventure. Adapt your story to their characters’ actions. Make sure everyone has a good time.