Using Inquiry Projects to Teach Language Arts

I knelt beside my sons’ toy closet, hauling out a strange menagerie of action figures. Here was a headless Tauntaun from Star Wars. There was the Smog Monster from Godzilla. How about the empty robe of a Nazgul from Lord of the Rings, or the Pokemon that kids call Gyarados but that most adults couldn’t name—let alone describe?

“What are you doing with all those old toys, Dad?” asked my youngest son.

“Teaching descriptive writing,” I replied cryptically.

Twenty-four hours later, I arrived in Chicago at the Annual Convention of the National Council of Teachers of English, towing that huge suitcase full of weird action figures. I met PBL teacher Cindy Smith there, and the two of us presented “Using Inquiry Projects to Teach Language Arts.”

Cindy and I have collaborated over three years in her project-based-learning classroom, and we’d come to the NCTE convention to share eight of our projects and inquiry experiences.

Despite the lateness of the hour (last session on Saturday) and the location (it was on a half floor that most of the elevators didn’t stop at), we had 30 or 40 educators at the session, and we dived right in.

Police Sketch Artists

For the first inquiry experience, I asked the teachers to pair up. One partner would be a police sketch artist, drawing a picture of a culprit who had committed a crime. The other would be the eyewitness who saw the perpetrator. The two partners sat back to back so that the sketch artist couldn’t see the perpetrator, one of the toys withdrawn from my rolling case and handed to the eyewitness.

The room filled with a sweet buzz of laughter and discussion as the eyewitnesses struggled mightily to describe what they held, and the artists struggled mightily to draw what they heard. After they were done, we compared the toys to the drawings and discussed which descriptive strategies had worked and which had not. We talked about the challenges inherent in describing anything—and the teachers all had ideas, because they all had just struggled to create clear descriptions.

I use this “Police Sketch Artists” inquiry experience to introduce students to description. The activity immerses students in a playful atmosphere of experimenting, testing, trying. They have to describe and draw before they can even think about writing. I ask the artists, “What descriptions were most helpful to you, and why?” I ask the eyewitnesses, “What was the biggest challenge in describing, and why?” The answers flow, with many unique insights, and everyone is ready to learn, because everyone is engaged.

Photojournalism Project

After this experience, Cindy launched participants into a photojournalism project, asking the driving question, “How does a picture capture the history of your community?” In her class back home, she had asked students to work with our local library and historical society to find photos that contained evidence of the way the city developed. Students could also take digital cameras into the community to take their own present-day pictures. Afterward, they had to assemble a photo-essay of both historical and current photos and write a composition that described what the photos showed.

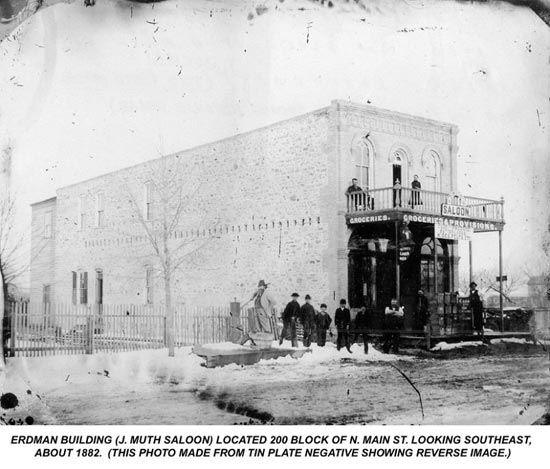

Cindy presented a sample collection of these photos and asked teachers to use them to tell the story of Burlington, Wisconsin. Whenever a teacher offered an observation, Cindy asked the person to provide evidence from the photo to support the claim—just as she had prompted her students. Below, I have included sample answers from some of the participating teachers.

Comment 1: It’s cold where you come from. Look at all the snow.

Comment 2: Your city was around in 1882, according to the caption.

Comment 3: Not a lot of diversity there. All white, all men except the little girl on the balcony.

Comment 4: Your city is not in a dry county, since that’s a saloon.

Comment 5: It also says “Groceries” and “Provisions.” So this place looks kind of like an outpost in 1882.

Comment 6: Why is the building so narrow?

Comment 7: It’s on Main Street. They’re going to be building more storefronts like that.

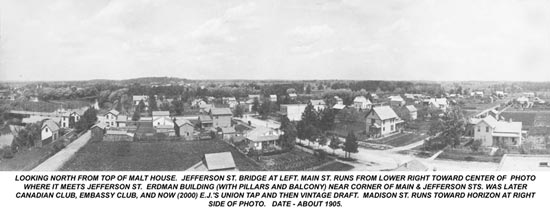

Comment 1: The caption says the photo’s taken from the top of the Malt House, looking at the J. Muth Saloon on Main Street.

Comment 2: The street doesn’t look very main. Look, the saloon is the only storefront.

Comment 3: A malt house is part of a brewery.

Comment 4: (From me) In fact, that was the Jacob Muth Malt House.

Comment 5: Mr. Muth has a business on either side of Main Street. He was quite the businessman in your city.

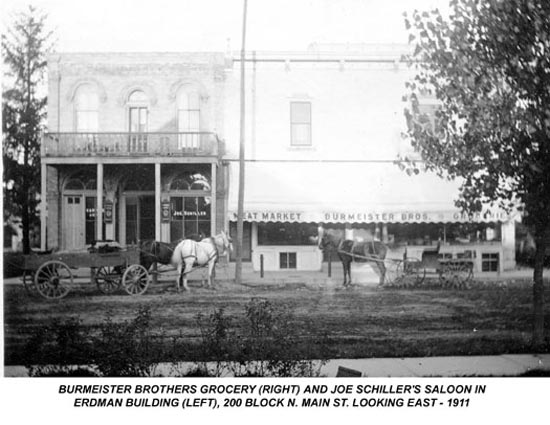

Comment 1: Now there’s a grocery store next to the saloon. You can’t get your meat and eggs in the saloon anymore.

Comment 2: And it’s not J. Muth’s Saloon anymore.

Comment 3: This is 1911. That’s about 30 years after the first photo. Maybe Mr. Muth is dead.

Comment 4: It looks like they finally put up another storefront on Main Street.

Comment 5: Yeah, but it’s not narrow like the other one. Maybe the land there wasn’t quite as valuable as Mr. Muth thought. Location, location, location.

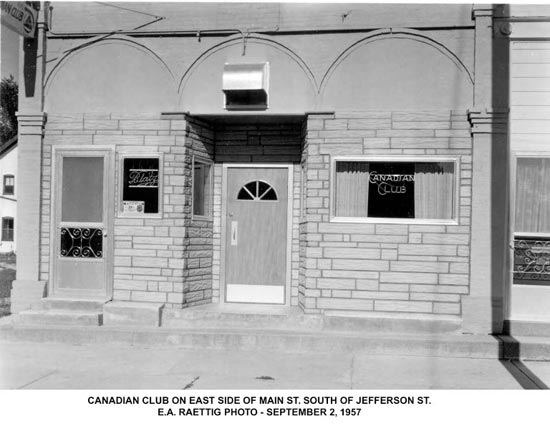

Comment 1: Uh, oh. What happened to the windows?

Comment 2: Maybe somebody got slid along the bar and crashed through, like in the old Westerns.

Comment 3: The old saloon’s looking pretty sad in 1957.

Comment 4: (From me) And by this time, the Jacob Muth Malt House has been sold for back taxes to a local community theater. I’m actually a member of that theater group, which still puts on plays at the Malt House.

Comment 5: So, Main Street really didn’t turn out to be the center of town.

Comment 1: That’s the place now?

Comment 2: It’s still a saloon. Imagine that—for 130 years, that building has had just one use.

Comment 3: The grocery store next door is gone. Just a parking lot.

Comment 4: I like the dentist office next door.

Of course, I didn’t write down these comments word for word as they were spoken, but you get the general sense of how the conversation went. With just a few prompts, teachers who knew nothing about Burlington provided some really interesting insights into the history of the city. They used their visual literacy to explore through inquiry. And they “experienced” a project they could use in their own classrooms.

The Rest of the Story

Cindy and I presented six other projects and inquiry experiences, which I will share in later posts. From these two examples, though, you should have a good sense of what it was like to be in the sessions at NCTE and AMLE (formerly NMSA).

If you’d like to download the Powerpoint presentation and handouts from the session, just go to www.thoughtfullearning.com/NCTE2011.

We want to hear from you! What inquiry experiences have you used in your classroom? What projects do you use to teach your subject? Please enter your comments below.

Comments

Engaged Learning

I attended your session in Kentucky last November and I am pleased to share that I use many of your ideas and incorporate them into my unit plans in a variety of ways. Students are engaged and quite frankly, hooked on the learning with many of the projects. One I recently added to the list was: This is a Photo of Me. I combined and infused ideas from your presentation and continue tweaking ideas to create a project entitled: This is my story. Thanks for the great ideas!

Post new comment