Newsletter Article: Making Your Claim

Web Page: Counter-Argument

Web Page: What is a counter-argument?

Web Page: Ethos, Pathos, Logos

Web Page: Socrates

Web Page: Socratic Questioning

For essays, speeches, debates, meetings, or intense discussions, you may need to organize your thoughts and defend them against people who might not agree with you. To do your best in these situations, follow the process outlined in the next few pages. Remember that arguments stem from a claim or position supported by compelling evidence—evidence that persuades the reader or listener to accept a point of view.

When you need to build an argument, use the seven C’s to develop and support a position about a specific topic:

Your Turn Which step in the process outlined above corresponds to the questioning phase of the inquiry process? Which steps correspond to planning? Which steps relate to research? In what ways does building an argument require the inquiry process?

Before you can build a strong argument, you need to analyze the communication situation. Ask yourself the following questions:

Sender: I'm writing less as a high school student and more as a concerned American citizen.

Message Subject: I'm writing about the national debt.

Message Purpose: I'm calling for spending cuts and tax increases to address the debt.

Medium: This should be a letter to the editor, so it can reach a general audience.

Receiver: My audience is all Americans who are worried about federal fiscal responsibility.

Context: This message will appear in a newspaper locally, and it could be picked up by a wire service to appear in national papers.

Your Turn Think of the topics you are studying in your classes. Which topic do you feel most strongly about? What position would you most like to argue for? Analyze your communication situation by answering the questions above.

Before you can convince others, you must be clear in your own mind about your position. What are you trying to prove? Why do you feel the way you do? What kind of proof do you have? In addition, you should consider both sides of the issue. To do this, set up a pro-con chart like the one shown here:

Pro | Con |

Reducing the national debt . . .

| Reducing the national debt . . .

|

Your Turn Create a pro-con chart, arguing for and against your position. Thoroughly explore both pros and cons. You will need to understand all perspectives to make a convincing case.

After you have thoroughly investigated an issue, you are ready to construct a claim about it. Arguments develop three types of claims:

| The national debt threatens the future of our nation. |

| A balanced budget would be the best gift we can give our children. |

| The federal government must cut spending to reduce the national debt. |

To formulate a claim, name your subject and express the truth, value, or policy you want to promote.

Subject | Truth, Value, or Policy | Claim (Position) Statement |

The national debt | downsize post-war military spending and social programs | To reduce the national debt, the U.S. government must cut wasteful spending. |

After stating a claim, you must support it. Different types of details provide different types of support:

| Each taxpayer's portion of the U.S. national debt is over $140,000. |

| The debt-ceiling debacle of 2011 caused the U.S. credit rating to slip. |

| A person who makes $46,000 can’t spend $71,000—but the government does. |

| “We must not let our rulers load us with perpetual debt,” said Thomas Jefferson. |

Your Turn (1) Use the formula above to construct a truth, a value, and a policy claim about a subject you feel strongly about. (2) Choose one of your claims and research it. Write down one of each of the four types of supporting details listed in the chart above.

Any debatable issue has at least two, and often many, points of view. When you build an argument, you need to consider alternate positions. Just as you have gathered support for your position, those with other perspectives will have gathered objections. Start by identifying them.

Objection 1: | The debt matches our gross domestic product, which means that the debt has not yet reached an unmanageable size. |

Objection 2: | The boom of the '90s balanced the federal budget, and the next boom will balance this budget. |

Objection 3: | The time to cut government spending is not during a recession but during a boom. |

Your Turn Reverse your thinking. Imagine that you strongly oppose the claim you made and researched on the previous pages. List at least three serious objections to your previous position.

Ignoring the objections to your argument weakens rather than strengthens it. You need to face objections head-on. The following strategies have been applied to each of the example objections above.

| If our gross domestic product goes down, our debt goes up as we try to stimulate the economy. Allowable debt can't be based solely on GDP. |

| It is true that the boom of the '90s resulted in a balanced budget, but a balanced budget fixes only that year's deficit, not the compounded national debt. |

| Yes, during a recession, government spending is needed to get the economy moving again. Now that the recession is over, we need to reduce spending. |

Your Turn Answer each of the objections to your own claim that you listed in the previous “Your Turn” activity. Either rebut the objection, recognize part of it but overcome the rest, or concede and move on.

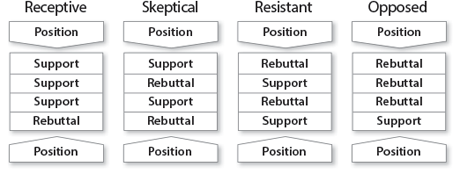

How you structure your argument depends a great deal on how receptive or resistant your audience is. For a receptive audience, you can provide support up front and rebuttal of objections near the end. For opposed audiences, you may want to start with rebuttals.

Your Turn Think about the audience for the position (claim) you chose to work with on pages 103-104. How receptive or resistant are they? Which of the structures above would you use to craft your argument? Or would you use a different structure? Explain your answer.

Classical rhetoric, or the art of persuasion, prescribes three ways to appeal to your audience:

The most persuasive arguments may use all three types of appeals—but always responsibly. Each of these appeals can be abused, as you will see in the section on logical fallacies (pages 108–112).

Your Turn You’ve learned about using logic (logos) to connect with the reader. Now consider what your audience wants or needs in order to make an emotional connection (pathos). How does your position help them get what they need, want, or expect?

Complete your argument by stating your main point in a new way and connecting it to the future. Leave your audience with a strong final thought.

You’ve learned how to build a compelling argument. There’s also a technique for examining arguments and deepening thinking.

The Greek philosopher Socrates examined arguments through questions, pushing students to use logic to deduce answers. Socratic questions are especially useful for probing the thinking of opponents in a debate.

Your Turn With a partner, discuss a current issue that you are studying in class. Use Socratic questions occasionally to deepen the discussion. Which questions were most helpful? Which were least helpful? Why?

Newsletter Article: Making Your Claim

Web Page: Counter-Argument

Web Page: What is a counter-argument?

Web Page: Ethos, Pathos, Logos

Web Page: Socrates

Web Page: Socratic Questioning

© 2014 Thoughtful Learning