Web Page: Inquiry Process

Web Page: Guiding Questions

Web Page: Encouraging Curiosity and Inquiry Learning

Web Page: Brainstorming

Inquiry is a process that starts with questions, which create a space for answers. You plan how you will find answers and then conduct research, making new discoveries along the way. Afterward you use what you discovered to create something new. Finally, you improve your creation and present it to others. This chapter provides an overview of this process, and the chapters that follow explain each step.

You’re just starting out, so now is the time to ask questions. Anything is possible. Ask creative questions, simple questions, deep questions. Imagine, wonder, dream, brainstorm, hope. | Question |

Next, choose one possibility and plan how you will make it happen. Decide what you want to do, what your goals are, how much time you have, and what resources are available. | Plan |

Then do the research. Follow your plan, use your resources well, and gather complete information and helpful details. This will involve working with media, technology, and people. | Research |

As you create, use your discoveries to make something new and amazing. Build. Write. Design. Sculpt. Record. Don’t worry about perfection at this point. Just get something out there. | Create |

After creating something, you need to evaluate it. Does the end product meet your goals? Does it do what you want it to do? What works well? What could work better? How can you improve what you created? | Improve |

Once your work is ready, present it to your audience. Afterward, ask yourself if the work is everything you wanted it to be. What did you learn as you worked on this project? | Present |

Your Turn How are the steps in the inquiry process related to each other? Why do you think they are ordered in this way?

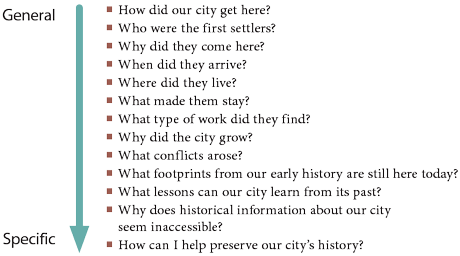

The process of inquiry is born out of curiosity. It begins with a question or an observation, which triggers more questions. As your questions become more pointed or specific, your thinking deepens. You seek a guiding question to drive your inquiry.

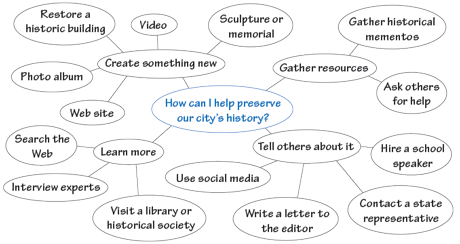

Once you arrive at a guiding question, consider how to answer it. Don’t limit yourself, either, because at this point, all ideas are open for exploration. Brainstorming is one strategy for gathering ideas. Let your mind wander. If possible, invite others into the brainstorming process. The more minds the better.

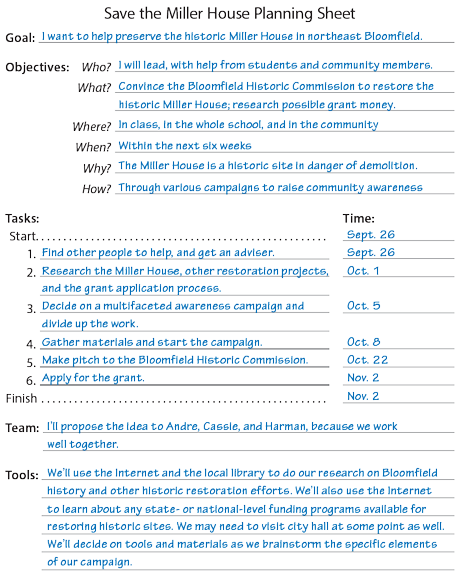

After considering the ideas you brainstormed, it’s time to decide what you want to do and how to do it. Planning involves setting goals, listing tasks, scheduling time, and gathering a team and tools. A planning sheet can help.

Your Turn Go to thoughtfullearning.com/h338 to download your own planning sheet and complete it for a project you are working on. (Also see page 361.)

Doing research is vital to finding the answers you need. Depending on the project, you may use primary sources, secondary sources, or a combination of the two (see pages 376–391), but always use a reliable note-taking system to record the information you glean. Below you will find two examples of electronic note pages.

What role did the Miller House play in Bloomfield’s history?

Sources:

Goodspeed’s History of Southeast Missouri

The Daily Statesman

Are there any grants or funding opportunities for preservation projects?

Your Turn Research specific questions related to a project. Take notes on note cards, in a notebook, or with an electronic note-taking system.

Having built a solid foundation of information about your topic, you are ready to carry out your project. Remember that turning an idea into a reality is both exciting and challenging. Some ideas will take more work than you had planned; other ideas may fizzle. That’s okay. Learn from these experiences and move on. At this stage, you need to create just the first version of the project, not the final version.

After completing your project, you must properly evaluate it and make any necessary improvements. Leave enough time for this important step. Some improvements, especially those pertaining to accuracy or clarity, will come from critical thinking. Others will be more creative. An improvement plan like the one below can help.

Name: Shantel Bailey

Project: Miller House Restoration (Slide Presentation)

Cutting: What part or parts do not help me reach my goal or objectives? How can I make my work simpler, more concise, cleaner, or clearer?

Problem: Some of the slides are messy and contain too much text. Also, I found out the grants are no longer federally funded, so those slides are mostly useless.

Plan: I’ll divide some slides into two and cut unnecessary text that may distract from the oral presentation. I’ll also cut the information about defunct grant opportunities.

Rearranging: What part or parts are in the wrong place? How can I rearrange my work to make it more effective, efficient, and smooth?

Problem: There isn’t enough background—I should do a better job of setting the scene before making my final pitch.

Plan: I will move the historical information and photographs closer to the beginning of the presentation in order to make my plea more persuasive.

Reworking: What part or parts need to work better? How can I rework them to achieve my goal?

Problem: The photographs of the house in its present state are a bit fuzzy and not centered.

Plan: I’ll ask Andre to take some more pictures since he’s a really good photographer.

Adding: What is missing from my work? How can I add just what is needed?

Problem: The process for saving the Miller House seems like speculation. I need information about a similar historical restoration that succeeded.

Plan: I’ll do some research, find a similar project, and create a slide about it.

Your Turn Go to thoughtfullearning.com/h341 and download an improvement-plan template. Use it to brainstorm improvements to a project you are working on. (See also page 421.)

After you’ve planned, researched, created, and improved your project, you are ready for the payoff: presenting your work to an audience. You could enter a design project in a contest or display it in your local library, a coffeehouse, or some other public place. You could present an audio-visual project on social media or in a subject-specific blog. And there are other possibilities, of course.

Shantel and his team sent a letter to the editor of their local newspaper. A week later, they appeared before their historical commission and delivered an oral presentation and slide show. All the while, they used social media to promote their ideas. These efforts made the community aware of the project and convinced the preservation commission to pursue funding options to restore the Miller House.

Web Page: Inquiry Process

Web Page: Guiding Questions

Web Page: Encouraging Curiosity and Inquiry Learning

Web Page: Brainstorming

© 2014 Thoughtful Learning