Web Page: American Rhetoric: Top 100 Speeches

Web Page: The Single Best Idea for Reforming K-12 Education

Web Page: 50 Demonstration Speech Topics

Does the speech have a clear focus and position on the topic?

Does it achieve the purpose?

Do test audiences get the point? Are they interested?

Remove extra words or unneeded parts.

Rearrange details that appear out of order.

Rework parts (beginning, middle, ending) that don’t work well.

Add stories, statistics, quotations, or other support as needed.

In the following speech from an all-school convocation, a speaker presents the value of student-centered education.

Education Reform: What Google Taught Me

The beginning gets the audience’s attention and introduces the topic.Hello, everybody. My name is Jason Carter, and I’ve got an idea for making things better for high school students here and nationwide.

I’m going to show you a pair of photos, and I want you to study them for a few moments. The photo on the left shows a modern factory

in China. The photo on the right shows a typical school in the U.S. Do you notice how these two places follow the same model?

In a recent Forbes article entitled “The Single Best Idea for Reforming K-12 Education,” Steve Denning writes, “To my mind, the biggest problem is a preoccupation with, and the application of, the factory model of management to education, where everything is arranged for the scalability and efficiency of ‘the system,’ to which the students, the teachers, the parents and the administrators have to adjust. ‘The system’ grinds forward, at ever increasing cost and declining efficiency, dispiriting students, teachers, and parents alike.” The middle develops the main idea, using words and images to persuade the audience. All around us, the world is transforming from an industrial economy to an information and innovation economy. It’s time for education to catch up.

All around us, the world is transforming from an industrial economy to an information and innovation economy. It’s time for education to catch up.

Here, by the way, is a shot from inside the UK office of one of the most innovative companies in the world: Google.

In the school photo, everyone was doing the same thing—probably taking a standardized test. In this photo, everybody is doing something different: writing code, playing a game, watching a film, contributing

to a schedule. In the previous picture, everyone was sitting in rows of identical, bland furniture. In the Google photo, some people are sitting, some are standing, some are reclining. The furniture comes in all shapes and sizes and colors. It invites you. The school photo has no technology in it. Even cellphones are prohibited. The Google shot shows all kinds of technology, both native to the room and brought in by the users. The school photo raises my blood pressure just to look at it. The last one makes me feel, “I want to be there.”

Shouldn’t schools aspire to be places that students want to be? If students are engaged at school, they will focus and work and contribute and learn. If they aren’t engaged, education is an uphill battle.

So what can schools learn from companies like Google and Apple? These companies focus on being useful and providing a great user experience. Once again, shouldn’t schools want first and foremost to provide an enriching education—one that clearly helps every student rather than one that begs the question, “Why do I need to know this?”

A slide summarizes the spoken points, helping the audience to focus.

Here are some suggestions for creating a positive educational experience for students:

Many of the factory jobs like those we saw in the first photo have shifted overseas, so I need to be ready for a different kind of workplace. I need to be prepared to think, innovate, interact, and take responsibility for my own progress. The changes I’m suggesting would help me and my whole generation do so.

Your Turn Think about ways your school is changing or evolving. Then think about other changes that might improve your school experience. Write these thoughts down and share them with a classmate.

The speech on the previous pages is written out word for word in manuscript form. This format works well when every word has to be right. For other situations, try one of the following speech formats.

An outline provides an organized listing of the main points to be covered in a speech. Here is the speech from the previous page in a simplified outline format. (Also see page 374.)

Convocation Speech

A. Show two factory model photos.

B. Show photo of Google office.

A. Discuss differences:

– All doing same test vs. each working individually

– All in strict rows in uniform furniture vs. standing, sitting, lying

– No technology vs. many forms

– No one wants to be there vs. everyone wants to be there

B. Create a school that provides an enriching education and great user experience.

C. Outline how:

– Make us welcome.

– Make us active.

– Let us use tech.

– Let us solve problems.

– Let us innovate.

– Let us think, innovate, interact, and take responsibility.

For simpler, shorter speeches, you can create a simple list of main points.

Your Turn Create an outline, a list, or a manuscript for a speech of your own.

In a demonstration speech, you show how to do something or how something works. The following speech explains how to use the quadratic formula to solve quadratic equations.

How to Use the Quadratic Formula

The beginning introduces the topic and provides the first visual.

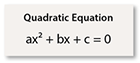

If you have taken algebra, you’ve run up against the quadratic equation. It looks like this: a times x squared plus b times x plus c equals zero. Often you can solve this equation using the FOIL method, but when you have fractions, decimals, or radicals, it might be easier to use the quadratic formula to solve the problem.

The middle provides the formula and gives step-by-step instructions for using it.

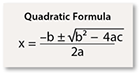

The quadratic formula looks like this: x equals negative b plus or minus the square root of b squared minus 4 times a times c divided by 2 times a. I know, that sounds really complicated, but it’s just a matter of plugging in the terms from the quadratic equation and doing your calculations. Note, however, that the plus or minus sign before the radical means that you need to calculate the formula twice to get two different answers.

The presenter runs through an example.Example Problem

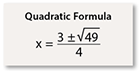

Imagine that we have the following quadratic equation that we need to solve: 2 times x squared minus 3 times x minus 5 equals zero. In our original quadratic equation, there were no minus signs. That means our b and c variables are negative. So our variables are a equals 2, b equals minus 3, and c equals minus 5.

Step 1: We start by plugging these variables into our quadratic formula. Remember that negative b is the opposite of b, so in this case, negative negative 3 will be positive three.

Step 2: Next, we need to run our calculations. Remember your order of operations! We have to start by figuring out the value of the radical. First, we square negative 3 to get 9. Then we multiply negative five times negative two times four to get negative 40. So 9 minus negative 40 equals 49. Also, 2 times 2 equals 4 (and as we said, negative negative 3 is just 3).

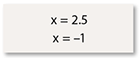

Step 3: Now, we have to run calculations twice, one with the plus sign and once with the minus sign. The square root of 49 is 7, so 3 plus 7 is ten divided by 4, which gives us 2.5. That’s one answer for x. The other is 3 minus 7, which is negative 4 divided by 4, which is −1.

Step 4: Finally, we can graph the equation as a parabola that crosses the x axis at points 2.5 and −1.

Because the quadratic equation creates a parabola, we can use it to predict the arcs of moving objects, from cannon balls to comets. This equation also helps aeronautical engineers predict how air will move over a plane’s wing. Think about that next time you see one hanging in the sky!

Conclusion

At first glance, the quadratic formula might look too daunting to be useful. But as you can see, it makes calculating quadratic equations just a matter of plugging and chugging.

Web Page: American Rhetoric: Top 100 Speeches

Web Page: The Single Best Idea for Reforming K-12 Education

Web Page: 50 Demonstration Speech Topics

© 2014 Thoughtful Learning